→ IT

On November the 6th, the city of Brussels has been the theater of one of the largest demonstration since decades. As the media observed, among the 150,000 protesters many wore the orange uniform of the dockworkers of Antwerp, one of the main ports of the EU. Several hundreds of them clashed for hours with the police. Many reports have pointed out the presence of extreme right sympathizers among the dockworkers involved in these clashes. However, this interpretation, which emphasizes an opposition between the casseurs and the peaceful demonstrators, runs the risk of neglecting the reasons of the anger expressed by the dockworkers and of obscuring what is happening inside and around the ports. Rather, it is worth reflecting on their presence in the demonstration and on their reiterated activism. The ports are, as a matter of fact, the core of the European trade: the 90% of commercial traffic between the EU and the rest of the world, and the 40% of the intra-EU traffic pass through them. The port of Antwerp is in direct competition with Rotterdam and Hamburg. Hundreds of thousands of containers coming from Asia, particularly from China, land in these ports and supply the productive chains that, from France to Central Europe, including the «German locomotive», reach the newly industrialized areas of Eastern Europe, Poland in particular. These ports are the connectors between Europe and the rest of the world in the global age. It is not a coincidence that the areas between these ports and the inland are characterized by the highest logistic intensity.

Antwerp and Europe in global logistics

In order to give an idea of the relation between the trade volumes that cross these ports and the current global production balance, it is useful to mention that Rotterdam, the main European port in terms of containers, finds itself in the tenth place in the top world container ports, following nine Asian ports and Dubai. Two of those nine (Shanghai and Singapore) manage a volume three times bigger than Rotterdam and another two of them (Shenzhen and Hong Kong) manage almost a double volume. After Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp finde themselves just at the 15th position, while Los Angeles, the main US port, is at the nineteenth position. Globally, China and the United States are the major exporters of containers, but China exports three times the amount of the US containers. China and the US are also the major importers, but the US surpasse China by one third. These data return only a partial image of the maritime traffic, because they exclusively refer to containers traffic and therefore do not consider the movement of raw materials and fuel, which are transported by ships and by other means of transportation. However, they allow us to identify some of the main axes of global production. The containers piled on the docks of these ports host every kind of products; both finished and semi-finished goods or components that today make up the majority of worldwide trade. The ports and the logistics chains to which they are connected should be understood as an integral part of the overall production process and not, as is often the case, as something external, which comes after the end of production. In order to understand the work of the Antwerp dock workers, it is useful to mention that out of the total volume handled by the port, around the 54% consists of containers and the 37% of materials transported by bulk vessels (such as liquid, gas or other fuels or chemical or solid compounds, such as coal, gravel, or other materials). The remaining 9% is composed of other materials not packed in containers, and wheeled transport.

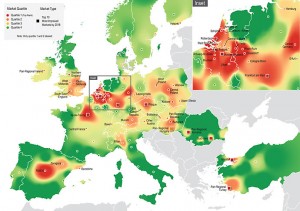

A survey among the logistics operators in Europe, realized by the global logistics giant Prologis in 2013, indicates the Antwerp-Brussels area as the second most favorable area for investments in the logistics sector, after the area of Venlo in the Netherlands, near the border with Germany. The ranking by Prologis works as a sort of rating for a sector that responds more and more to a financial logic, and is based on four indicators: proximity to customers and suppliers; labor and government; real estate; infrastructure. It is interesting to observe how the desirability indexes of the various sites are structured. While in the area of the Rhine-Ruhr region (fourth) what matters the most is proximity to customers and supply chains, in Venlo «labor and government» are the most attractive factors. «Labor and government» are a weak point for Rotterdam, while the Antwerp-Brussels area is positioned halfway between this two. Venlo has also the highest score with regard to infrastructure, immediately followed by Rotterdam. Antwerp-Brussels and the Rhine-Ruhr region are respectively third and fourth. Again, we are talking about European regions in which the first multi-modal communication networks have been realized, including high-capacity freight transport rail (HS/HC) and efficient highway networks, linked to advanced logistics parks. We note that the prediction of Prologis for 2018 largely confirms the first four positions, while the Pan-Regional Romani – an area corresponding to the triangle Timisoara, Bucharest and Brasov – should occupy the fifth place.

However, to understand the protests of the Belgian dock workers, we must above all look at the competitive differences between EU ports in relation to «labor and government». This criterion rests on four indicators: labor availability and flexibility; wages and benefits; regulations; incentives. The labor cost is an issue that, for the moment, is balanced by other factors, including regulations and incentives. What should be emphasized here is that the areas taken into account, while serving the same market, are now characterized, not only in the logistics sector, by very different organizations of labor, wage conditions, regulations and incentives. In this situation, even though they share with other sectors the deterioration of the workers’ bargaining power, in the main ports such as Antwerp workers are still able to organize and resist these processes collectively.

Port labor and the two-speed Europe

More than 500 thousands workers are working today in European ports, but the statistics differ, ranging from 1.5 million, including the spin-off of the close dockland, to approximately 110 thousands dock workers in the strict sense. This depends both on their classification, and the high rate of precarity and fluctuation of the number of workers requested for the dock services. Anyhow, these numbers are not so high if compared with other productive sites and in particular if one considers the relevance of their function in the productive chain. This is related to the massive automation and the introduction of containers, which in the last decades led to the dominance of giant ships along the main routes. More or less specialized workers, working with large machines and under strict and increasingly standardized control procedures, largely replace traditional dockworkers crews. The major ports appear as huge spaces where the movements are slow and it is difficult to see the men at work. Considering the quite successful rhetoric about the end of the factory work, however, it is necessary to stress once again that the automation of ports and the extensive use of digital technologies in their management and organization do not indicate at all the irrelevance of the manufacturing labor. On the contrary, automation and digitalization are two features of a reorganization of production on a global scale, which must take into account that the commodities that flow in large ships, including the containers and the ships themselves, somewhere must be produced. This happens increasingly in productive plants which reproduce naval gigantism: a known example of that is Foxconn, the global electronics giant, whose main factory in Longhua employs more than 250 thousands working men and women and includes a hospital, several dormitories and sports fields: a real factory town of gigantic size. The fact that there are people who still use the instruments produced in places like Foxconn to declare the progressive irrelevance of the factory work, can be explained only by the removal of the global dimension of contemporary production.

These numbers show that the trade which is passing through the ports allows the EU to be one of the main players on the stage of globalization. The pivotal role of the several hundreds docks workers that we have seen in Brussels should be read in conjunction with this picture. Their main enemy, besides the policies of the Belgian government, is the EU attempt to liberalize the port policy at the continental level in order to overcome the current organization based on a national scale. Several reforms have already led to a general reconfiguration of the ports, turning them from public infrastructures into private systems, with a participation of private operators. In addition, as the case of Piraeus – by now largely managed by the Chinese operator COSCO – shows, national policies are not very helpful for dock workers in countries where the economic and political crisis has allowed the EU, together with national governments, to bring the neoliberal policies promoted through the ESM (European Stability Mechanism, better known as Bailout Fund) to more advanced levels of experimentation.

The old myth of the «camalli» – as the dockers are traditionally called in the Italian port of Genoa – persists, but today it takes the form of pockets of resistance besieged by global dynamics that are imposed by the force of the competition. However, it is clear that a liberalization imposed on a continental scale would hit even those ports where today the bargaining power of the workers is higher. This is not a novelty, but it would mark a step forward in the radicalization of the neo-liberal policies of the EU. In order to maintain an internal consensus, the national governments have tried until now to limit or mask the policies promoted on a continental scale. It is then evident that the «two speeds» of Europe are those of the neoliberal trend, on the one hand, and of the necessity of assuring social control and a minimum of consensus by those countries that have benefited from the trade imbalances and from the opening of the markets in the East, in particular Germany, on the other. The demonstration in Brussels shows that the Belgian government has obliged the Belgian people to recognizethe outcomes of policies which will inevitably break the thin national borders. Even though social movements and European trade unions still find it hard to understand it, Europe is a single market located in the global market and what happens in one part of it has effects on the other parts. The austerity policies for long time imposed to the PIIGS according to the rhetoric of «do your homework» have and will have consequences also for the countries whose citizens did not feel to be part of the students sent behind the blackboard. Brussels is the capital of Europe, but what Europe are we talking about? The leading role of the dockworkers in the Belgian anti-austerity mobilization tells us something. First, it suggests that there are at least two levels in the overall fight on a European scale: a more visible level, which mobilizes opinions and fragmentary debates, even though they are still organized on a national scale; and a less visible one, which is structural and accepted almost as a natural event, and which we shall sooner or later put in the spotlight. While the first level directly affects governments and European policies, the second has to do with the reorganization of production, which take advantage of the cacophony and of the different registers of the national and EU policies.

Get organized in the new European logistics

While unions and movements still largely frame their struggles in a national dimension or, at best, recognize austerity and the Europe of the Troika as their enemies, companies evaluate regional and national differences on the basis of different requirements that nevertheless respond to the same logic. While some unions say that European minimum wage, welfare and income are a problem, since vast differences exist among European countries, companies analyze these differences in order to exploit them and put them in communication for their own profits. In doing so, they contribute to produce those differences. Companies and governments, however, are not alone: they have to deal with the workers’ protests and the increasing mobility which, especially in Eastern Europe, stand in the way of their demands. Today these protests and this mobility have the features of a real movement that is not understood or considered as a whole both by social movements, who often choose to act a symbolic political antagonism, and by unions, often engaged in the defense of their own structure rather than in the organization of a collective response to the domination of capitalist command. The irruption of the docks in the streets in Brussels could function as a wake up call for both. This fact shows that perhaps today we should be able to look at the particular conditions of certain areas in order not to emphasize their specificity or uniqueness, but to grasp the general conditions which they help illuminating. At the same time, we should understand that, in a world already based on the generalized precarity of labor relations, rather than chasing the chimera of a universalization of rights or making general appeals to the unity of the struggles, it would be useful to undermine this basis. This is true even when the matter at stake is the defense of retirements or the indexing of wages, even though millions of workers in Europe have probably never heard of it. It is also necessary for social movements to understand that the national space that many of them declare to be willing to overcome, even though it remains the primary horizon of organization and imagination, it has been replaced neither by a generic European space, nor by a generic global transnational dimension. On the contrary, both the European and the global space are crossed by specific dynamics, which draw a new map of the power of command that capital exercises over labor.

Logistics is certainly a decisive sector and, in many cases, it is expanding in direct proportion with the growing mobility of production. Where logistics no longer serves the production, for example, logistics for consumption becomes central. Logistics has however also its own power through which it can impose new geographies of production and consumption, new ways of organizing social life and consensus. Thus, it is a mistake to reduce all of this to the circulation of commodities. At the same time, to think that today the power is in the hands of the workers of the logistics sector is naive. These workers are likely to be politically wiped out everywhere, as it the case of the US truckers and the dock workers of New York shows, unless we make an effort to understand their positioning along supply chains, which include also the sites where the commodities they transport are produced, and unless we place the logistics in relation to what happens around it, including the specific conditions of logistics workers, such as their status of citizens or migrants and their being women or men. In some situations, as in Italy, there still remains considerable space for improvement of the working conditions in a sector which is growing wildly. However, it is a mistake to think that an industry responding to a global logic can be hit by struggles which, according to the studies directing investments and decisions, are considered equivalent to any other chain disruptions, such as floods or terrorist attacks. Does this mean that they are right, and that these struggles are irrelevant? Quite the contrary: these struggles force the reorganization of a productive cycle, which is characterized at its core by the ability of maintaining a balance in a contingent situation and in the constant movement of its horizon. The same risk indices produced by large insurance companies also show how the rhetoric of the resilience of the global productive chains is actually sensitive to workers activism on a global scale. While there is an attempt to bring back the organization of labor, power relations and the government of mobility in the planning of future struggles, and while these struggle are imagined at least on a European scale, the major indication that comes out from logistics and the presence of the dock workers in the streets of Brussels is, thus, that it is crucial to organize ourselves keeping in mind the European geo-economy and its different mapping. It is in fact inside these maps, which nowadays move investments and affect the decisions of governments, that it will be necessary to make our claims and slogans heard. It is inside these maps that the different workers ought to be able to recognize themselves and use these claims beyond their specific conditions or provenance, and the political organization of labor must take the form of a communication able to pass from hand to hand as an instrument of struggle, turning mobility into a force to draw new maps against the capitalist command.

Logistics is certainly a decisive sector and, in many cases, it is expanding in direct proportion with the growing mobility of production. Where logistics no longer serves the production, for example, logistics for consumption becomes central. Logistics has however also its own power through which it can impose new geographies of production and consumption, new ways of organizing social life and consensus. Thus, it is a mistake to reduce all of this to the circulation of commodities. At the same time, to think that today the power is in the hands of the workers of the logistics sector is naive. These workers are likely to be politically wiped out everywhere, as it the case of the US truckers and the dock workers of New York shows, unless we make an effort to understand their positioning along supply chains, which include also the sites where the commodities they transport are produced, and unless we place the logistics in relation to what happens around it, including the specific conditions of logistics workers, such as their status of citizens or migrants and their being women or men. In some situations, as in Italy, there still remains considerable space for improvement of the working conditions in a sector which is growing wildly. However, it is a mistake to think that an industry responding to a global logic can be hit by struggles which, according to the studies directing investments and decisions, are considered equivalent to any other chain disruptions, such as floods or terrorist attacks. Does this mean that they are right, and that these struggles are irrelevant? Quite the contrary: these struggles force the reorganization of a productive cycle, which is characterized at its core by the ability of maintaining a balance in a contingent situation and in the constant movement of its horizon. The same risk indices produced by large insurance companies also show how the rhetoric of the resilience of the global productive chains is actually sensitive to workers activism on a global scale. While there is an attempt to bring back the organization of labor, power relations and the government of mobility in the planning of future struggles, and while these struggle are imagined at least on a European scale, the major indication that comes out from logistics and the presence of the dock workers in the streets of Brussels is, thus, that it is crucial to organize ourselves keeping in mind the European geo-economy and its different mapping. It is in fact inside these maps, which nowadays move investments and affect the decisions of governments, that it will be necessary to make our claims and slogans heard. It is inside these maps that the different workers ought to be able to recognize themselves and use these claims beyond their specific conditions or provenance, and the political organization of labor must take the form of a communication able to pass from hand to hand as an instrument of struggle, turning mobility into a force to draw new maps against the capitalist command.

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione