by RUTVICA ANDRIJASEVIC – from Hong Kong

She has just finishing her chalk drawing of an umbrella on the pavement in Admiralty, the main site of Occupy Hong Kong. Her classmates, Hong Kong University (HKU) undergraduates will join her later when they finish their classes held in the nearby Admiralty building. She has been part of the protests since the beginning and spent two nights huddled under the umbrella at the Admiralty square in order to support the occupation. Admiralty is were she feels happy and safe and part of the movement of her equals struggling for the same cause: for their voices to be finally heard by the government that she feels serves the objectives of the Central (Chinese) Government rather than that of Hong Kong.

She has just finishing her chalk drawing of an umbrella on the pavement in Admiralty, the main site of Occupy Hong Kong. Her classmates, Hong Kong University (HKU) undergraduates will join her later when they finish their classes held in the nearby Admiralty building. She has been part of the protests since the beginning and spent two nights huddled under the umbrella at the Admiralty square in order to support the occupation. Admiralty is were she feels happy and safe and part of the movement of her equals struggling for the same cause: for their voices to be finally heard by the government that she feels serves the objectives of the Central (Chinese) Government rather than that of Hong Kong.

Students have been playing a key role in Hong Kong’s mobilisation since the very beginning. While ‘Occupy Central’ has become in Europe and the USA the common term to refer to the Hong Kong protests, Occupy Central is actually only one of the groups, albeit important, partaking in the current wave of political activism. There are three major groupings that make up the students ‘body’: Scholarism, Federation of Students, and Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP). Scholarism is comprised of secondary-school students and was founded by Joshua Wong, one of the most visible figures of current protests. Scholarism came to the public attention in 2011 when it reacted to the Central (i.e. Beijing) Government’s push towards a ‘national education’ plan that would replace the current Hong Kong curriculum with one that is pro-Communist party and its own version of history (e.g. omission of the Tiananmen massacre). Federation of Students is comprised of university students and it is the biggest student organisation in Hong Kong. Federation is known for its political pro-democracy stance and it took part on the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 as well as in the class boycott in response to the massacre. The vice secretary of the federation, Lester Shum, is one of the spoke-persons of the current Hong Kong protests. Finally, Occupy Central with Love and Peace is a civil disobedience campaign and its participation in the protests is led by two university professors, Benny Tau of University of Hong Kong Law department and Chan Kin of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Sociology department, as well as the pastor Chu Yiu of the Chai Wan Baptist Church. The latter is a well-known human rights activist especially respected for its role in helping students flee mainland China after the Tiananmen Square massacre.

The main students’ demand is simple: they want universal suffrage for the chief executive election in 2017 as promised in the Basic Law (i.e. the mini-constitution for Hong Kong). Concretely speaking, this means they want for Hong Kongers to be able to elect their own Chief Executive rather than having to choose among those vetted by Beijing. As the things stand now, National People’s Congress proposed electoral reform would permit everyone to vote but the choice would be limited to an election committee of 1200 hand-picked by Beijing. This committee is likely to be composed mainly of pro-Beijing members. As the student drawing her protest art piece on the pavement in Admiralty put it ‘she wants a Chief Executive and a government that is chosen by Hong Kong residents and that has Hong Kong’s and not Beijing’s best interests at heart.’ In order to drive their point home and stress the non-democratic aspect of the current system, protestors placated the site with posters that ridiculed the number 689, which is the number of votes that sufficed for Leung Chun-ying to become Hong Kong’s current Executive in Chief. The struggle over the electoral system reflects a larger anxiety that Beijing is undermining Hong Kong’s freedoms that make the city so different from those in mainland China.

Under the ‘one country, two systems’ policy, Hong Kong is guaranteed in all matters except foreign affairs and defence ‘a high degree of autonomy’ from Beijing. The ‘one country, two systems’ refers to one country with two independent monetary systems, authorities and currencies as well as Hong Kong’s autonomy in matters of external economic relations (its status as a free-tariff zone among others), immigration control and other policies. Yet, as the matter of electoral reform shows well, the Central Government and Hong Kong residents interpret the notion of ‘high degree of autonomy’ quite differently. The future prospects are therefore worrisome for the protesters as by 2047, Hong Kong is to revert to full Chinese sovereignty, following the 50-year adjustment period from the Crown to the mainland rule. This has been laid down in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, according to which the region is to remain autonomous for 50 years after July 1, 1997, that day that marks the end of British rule in Hong Kong.

Yet, students’ protests are about more than the electoral reform. A poster pinned on an occupy tent makes the students’ discontent very clear by says ‘18 square feet = 8,000 HK$ per month’, which indicates the price of rent students are expected to pay if they want to live away from home (EUR 800 per month for 1.7 square meters). What is motivating the protesters then is diminished opportunities and high inequality rates. Yet, social inequality argument often goes invisible as the blame for inflated real estate prices is pinned onto the mainlander investments that are seen to lessen the available housing and driving up the prices, making properties out of reach even for well-to-do Hong Kongers. Social inequality in Hong Kong is stark: while it has one of the highest pro capita income in the world, around 19.6% of the population was living below the official poverty line in 2013 and the inequality in income distribution is the highest in the world of any developed economy.

The popular anger and the demands for redistribution and fairer policies, next to the withdrawal of Beijing’s electoral reform, are therefore to be seen as main motors of the protests. The protests have in fact provided Hong Kong residents with a forum to discuss social and political issues most pressing to them. To understand this it is important for those unfamiliar with the protests and Hong Kong to get a better idea of the occupy sites and their location. The main occupy site is Admiralty, an important intersection next to the main government building. A smaller site not far from Admiralty is Causeway Bay, the symbol of consumerism and the heart of the Hong Kong shopping scene and up-market fashion. Both of these sites are on Hong Kong island while the third site, of the similar size to the one is Causeway Bay, is in Mong Kok, in Kowloon that is located north of Hong Kong island and south of the mainland part of the New Territories. The occupation of these locations is strategic in that to occupy sections of the main roads means to block traffic and thus gain some control over the city. Protestors consider the sites of Causeway Bay and Mong Kok important in order to safeguard the main site of Admiralty by stretching of police resources. A major goal is also to diffuse the police force across different sites so that there is no enough police to crackdown a single site, in particular Admiralty. That’s why there is the line, ‘If Mongkok falls, Admiralty cannot hold for much longer’.

Such a distribution of sites is achieving much more than simply protection for the students as it is creating differentiated spaces for public debate for diverse types of participants. Let us take the example of Mong Kok where this dynamic is most visible. Mong Kok is a web of densely populated streets, shops and restaurants, where local residents are not affiliated with the students or Occupy Central but nevertheless came out onto the streets to support students after the police attacked them with 87 rounds of tear gas on 28 September. Students used the umbrellas to protect themselves and hence the term ‘umbrella revolution’ to describe the protests. So, imagine Mong Kok getting transformed from the most densely populated area of the world to a site there the main road is void of traffic and where, instead of a incessant flow of cars and buses, there are now barricades that enclose a space with tents, marquee and where anyone with anyone with an amplifier can speak and start a public discussion forum a within the zone. While this site is known for being independent of political organisations and parties and mirrors the traditional nature of the neighbourhood by setting up of shrines in order to protect the barricades, it is also the area that, unlike Admiralty, is not enclosed and where protesters are more exposed to the attacks by the police or thugs (also known as triads) paid to assault and disperse the students. Mong Kok occupy is as gritty as the neighbourhood itself: it rebuilds itself again and again whether after the attack by the thugs or current attempt by the police (on 17 October) to remove the barricades once and for all and that are proving unsuccessful as thousands of protestors are swelling in and effectively stretching the occupation to a larger area than before.

This ebbing and flowing of protesters has been a permanent feature of the mobilisation. Many journalists reported on the decreased numbers of participants there were perhaps even nights before one might have seen thousands. There is a very pragmatic reason to this and this is the working hours and the weather. People would gather, participate or simply check out the sites after working hours or classes and when the temperature drops slightly, as day temperature is typically around 30 degrees in this period. The other reason is strategic as it would not be feasible to keep a constant high numeric presence at all three sites. While the numbers of protestors who occupy Admiralty, Mong Kok and Causeway Bay permanently in their tents is rather low, the sites would swell with people when the main organising groups would call for it, usually following a specific event. One of these was, for example, when the Chief Secretary, Carrie Lam, called off talks between the Hong Kong government and student leaders planned for the 10 October, that many have hoped would helped towards solving the political impasse. Following the cancelling of the talks, students called for Hong Kongers to show support and gather in Admiralty and tens of thousands came. Temporary decrease of numbers of protesters then goes hand in hand with sudden increase of numbers when the situation requires it: it is in this sense that the protests resemble a wave that swells and recedes to swell again. Social media are being used extensively for this purpose so it is no surprise that one of the ways in which the authorities tried to stop the gatherings was by a cyber-attack against the Occupy Central website and by developing and launching a spy app.

Yet, perhaps the most astonishing dimension of the protests is the form these have taken. When speaking of protests, one usually imagines a march. Hong Kong protests are mostly sit-ins where students, families with children, elderly and others settle on the blankets, newspaper or shower curtains they have brought along, munch on the food they picked up at a nearby joint, get updates on the political situation as well as on practical matters (such as rubbish collection) and sing along to one of several songs that have become anthems of the movement. Another unusual feature for a city driven by individualism and profit is that the protest features a strong collective and shared dimension. For example, in Admiralty, protestors occupied the restrooms (both female and male) outside of the government building and supplied these with face and body creams, gels, wipes, shampoo etc. for everyone to use. On the square, one can get some small bites of food and water, for free. There is also a study area, with improvised desks for secondary-school students in particular to catch up on their homework. Additionally, in response to the accusations that that due to protests local shops are experiencing a decline of clients, protestors in Mong Kok have compiled a two page list of shops that helped the protests (via food, time, materials donations or just by making it possible to recharge ones mobile phone there) and distributed it widely in order to make visible the alliance between local business and the movement as well as to encourage protestors and allies’ support of these stores. The government has seized onto this abundance of supplies to argue it represented the evidence that ‘foreign influence’ is behind the protests.

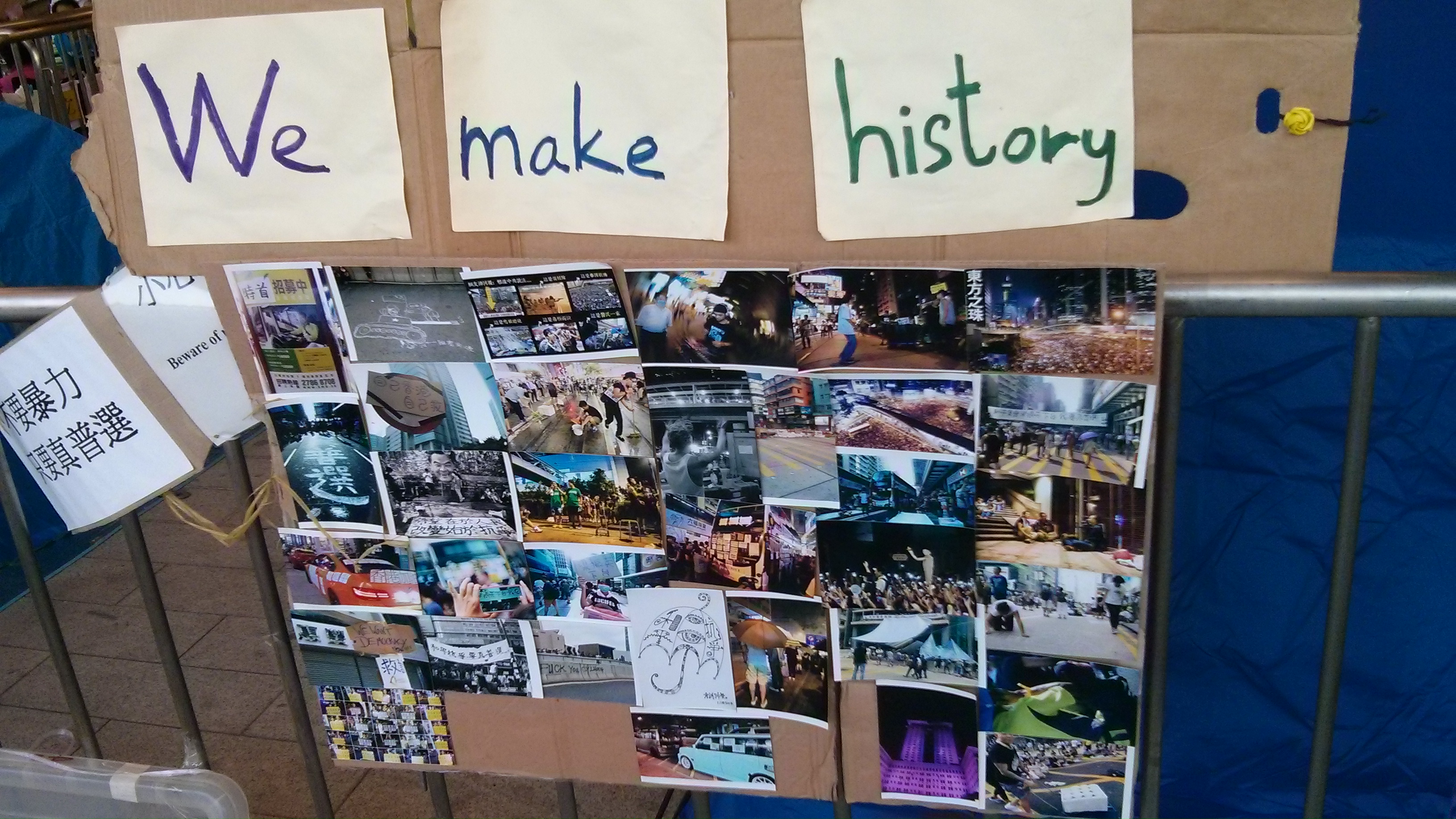

Following the confrontation between the protestors and the police in Mong Kok, Hong Kong government announced that they will meet and hold a two-hour talk with students’ leaders on Tuesday, 21 October. While many of the commentators believe that Beijing will not be making any electoral concessions to students, the relevance of protests goes well beyond the matter of universal suffrage. First, it points to Central Government’s difficulty/uneasiness to deal with the urban middle class. It remains to be seen how Beijing with grapple with this politically in the years to come. Second, the current wave of political activism has transformed city’s public space, even if only momentarily, into a site where to experiment with alternative, collective and not-for-profit forms of organising and life. Those public spaces that are commonly reserved for public speaking only when authorised by the authorities, such as the green space next to the main government building in Admiralty, have been appropriated by the protestors and are now used by a vast variety of Hong Kong citizens. Not far from there another group has been holding their ‘democracy classroom’. A project to save protest’s artefacts has already been launched: the ‘Lennon Wall’ on Admiralty covered in a rainbow collage of notes supporting the protests is being preserved digitally. Whether they manage or not to pressure Beijing to amend the electoral reform proposal, students have already ‘made history’ and offered to the citizens of Kong Hong a glimpse of a different city and of what activist citizenship looks like. As a friend said: ‘Hong Kong’s future looks brighter now’.

Note: For a comprehensive overview of Hong Kong protests see South China Morning Post’s site.

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione