di GABRIELLA – Leeds Solidarity Network

→ Italian

We publish the second part of the analysis of current transformations of welfare systems and government of mobility proposed by Gabriella from the Leeds Solidarity Network. The first part was published with the title: The Government of Mobility 2: The (United) Kingdom of workfare versus welfare for migrants Part I

We publish the second part of the analysis of current transformations of welfare systems and government of mobility proposed by Gabriella from the Leeds Solidarity Network. The first part was published with the title: The Government of Mobility 2: The (United) Kingdom of workfare versus welfare for migrants Part I

***

There is indeed a more or less obvious hypocrisy in the way in which other countries like Germany and the very EU institutions are responding to this rhetoric around ‘welfare abuses’. The hypocrisy of the EU appears in the double tone used in many of its latest statements and memos emphasising on the one hand the removal of barriers to free movement of workers and on the other re-assuring Member States of their legitimate right to protect themselves from alleged abuse on their welfare systems. The European Commission Memo (25 September 2014) reiterates the fact that after 3 months those who are ‘inactive’ including students and retired persons, need to prove that they have sufficient financial means to support themselves otherwise they will become an ‘unreasonable burden’ to the host country who will then be able to terminate their right of residence.

In the case of Germany, allegedly the champion of EU core principles, this is the very country that encourages the hollowing out of the freedom of movement principle of its social dimension, by its own recent intervention to limit the rights of ‘inactive’ migrants. These trends has been clearly expressed by the recent CJEU ruling on Dano v Jobcenter Leipzig 2013, regarding a Romanian national who was denied subsistence benefits for herself and social allowances and a contribution to accommodation and heating costs for her son. The implications of this judgement for MSs is that it reinforces their legitimacy of refusing social benefits to those who fail to provide evidence of attempts at integration in the labour market and it confirms the principle of punishing welfare tourism: Dano was denied her right on the basis that she was judged as having moved to Germany solely to obtain social assistance and yet, did not have sufficient resources to claim ‘a right of residence’. This circular logic between residence and access to rights reminds us the types of conditionality attached to non-EU migrants residence permit, who have to show to be financially self-sustaining/have a contract of employment upon entry to the country, and who have no recourse to public funds.

While the Dano judgement the CJEU confirmed the principle of employability as conditional to obtaining access to welfare, there are still some tensions across the different rhetoric and political agenda of the different member states. The ruling could be interpreted as a victory for Cameron to the extent that it supports the introductions of further measures to curb benefit abuse by EU migrants. On the other hand the ruling does not give rise to a wider debate about reforming freedom of movement from the German point of view. To understand what is going on in the government of mobility emerging from the different positionings of these two main countries of destination we may identify a divide between freedom of movement with equal treatment only for workers (German position) on the one hand, and free movement of labour only with no right to social rights even for worker (UK position). In fact while the British calls for a revision of the existing systems at EU level – including the availability of benefits to EU migrants who are in employment – the worker rights element of equal treatment remains a stronghold for the more Europeanist states such as Germany. Whether the ruling will make the former argument less likely to be heard it is something that is unfortunately far from being confirmed by the current proposals by both the Tories and Labour, who suggest that also migrant workers may be excluded from in-work benefits during the first years of their residence.

Moreover, while following the Dano judgement workers’ access to social assistance or social security seems to remain protected on paper, EU regulations already differentiates between categories of workers, whereby some, such as ‘posted workers’ (e.g. those posted only for short periods to work in the territory of another state) and contract workers employed via public procurement, remain excluded from such equal rights. In these cases the principle of equal treatment is ignored for workers on the basis of their special status as temporary or indirectly employed.

Anyway in both the German and UK cases the principle of equal treatment with the citizens of that country in terms of access to welfare is now officially scrapped for those migrants who do not prove their willingness to work or cannot support themselves. After all, the equal treatment principle was already made dependent on the right of residence and this could have always been revoked by a member state where a citizen became a burden on the State. This ‘right’ of expelling by MS has been widely exercised by states such as Belgium –which kicked out more than 7000 EU migrants in the past few years (See 2 Articles Connessioni Precarie). The capacity of expulsion and deportation by the governments of EU countries extended to EU migrants seem therefore to be further reinforced under the current climate and is worrying to see that further restrictions by the UK government predict that ‘EU nationals sleeping roughly or begging will be deported and barred from re-entry for 12 months’. This is a scenario that becomes even more realistic considering that since April 2014 EU migrants have been banned from Housing Benefits.

From Migration controls to welfare sanctions

Now, anyone can see how Member states’ push to restrain ‘free movers’ rights to social security and social assistance has a direct impact on EU migrants’ position in the labour market and indirectly on their bargaining power: those who cannot rely on the same level of social assistance as indigenous workers will be inevitably more keen to accept under-paid or temporary/flexible work. The key problem here lies in the very definition of who is economically active or inactive in a context where employment becomes increasingly intermittent while wage levels (especially those associated with the type of jobs that migrants usually do) are increasingly unable to allow a decent standard of living. At the very same time as people should have their social rights decoupled from the holding employment, which less and less appears to guarantee continuity and security of income, the exclusionary criteria of the UK (and increasingly European)’s workfare regime seem to be harsher exactly on those EU nationals who fall outside of the ‘worker status’, that is, exactly those who should be socially protected.

What lies behind the British government’s neoliberal logic of “economic freedom” applied to the fields of welfare and migration is in reality the compulsion to precarious work. Both in the case of national and migrant claimants, the increasing monitoring regime applying sanctions and cutting off benefits for claimants who do not take on work or comply with the strict rules imposed job centres, feeds into the machine of precarization that force individuals to be available and accept low paid and uncertain jobs.

Indeed since 2012 stricter criteria and conditionalities have been imposed on claimants together with a proper range of ‘punishments’ if they are found ‘cheating’ the system. Claimants are sanctioned by losing some or all of their benefit for a set amount of time according to the gravity of their ‘offence’ for breaking the rules for Jobseeker’s Allowance or Employment and Support Allowance. While the underlying criteria to obtain benefits is for claimants to demonstrate on a weekly basis to be actively seeking a job, there are a variety of situations where people are sanctioned simply for missing an appointment at the jobcentre, for not finishing a form, or because they take on voluntary work and cannot attend their meetings (this is ironic considering that voluntary work is often encouraged as a way to make one more ‘employable’!), for failing to attend a training or comply with directions from a Jobcentre advise. The coercive and disciplining nature of such a regime appears ruthless in its implications for jobseekers: reduction or full withdrawal of benefits may be applied in cases in which the claimant left the job voluntarily, lost the job for misconduct; failed to apply for or accept a job offered; failed to show availability to work or actively seeking it.

The only circumstance for the sanction not to be applied is if you can show that you had ‘good reason’ for the action that led to a sanction being considered. But the nature of this ‘good reason’ is not defined in legislation. While this theoretically allows for some flexibility in judging individuals according to their circumstances (e.g. disabilities, mental health, their role as carers…), there is a growing preoccupation that front-service workers’ impartiality can be hampered by the fact they are put under pressure and themselves target of disciplinary assessment if they do not take enough people off the registers and increase the number of benefits removals. Evidence has been reported that staff is even given targets to demonstrate that the system is ‘working efficiently’. Combine this with the increasingly detailed questions that migrant claimants are subject to because of their specific status, it is easy see how those with little knowledge and capacity to deal with the system on the basis of poor language skills and lack of support such as recently arrived migrants, are those mostly exposed to sanctions.

Once again, the UK management and differentiation of welfare represents a clear case of how social benefits always come at a price (exploitative low paid jobs) whereby the concession of unemployment allowance constitutes a central mechanism of the government of mobility.

From the edges of the workfarist government of labour and mobility…a potential terrain for unity?

The figure of the employable migrant who can exercise her right to free movement only in so far as she demonstrates her ability to ‘integrate’ in the labour market and avoid becoming a financial burden for the host state encapsulates the contemporary modalities of control of labour mobility and the management of welfare rights. This logic makes free mobility and residence rights conditional upon migrants’ ability to labour, if not strictly on the possession of a contract of employment. It mirrors the old principle of dependency created by the work permit system, which for long has been applied to non-EU migrants. What would a ‘genuine prospect of work’ after the first 3 months of receiving benefits for migrants in the UK mean, after all, if not that the person has already been offered a job? At best, the loose definition of a ‘genuine prospect of work’ as a condition to gain the status of jobseeker in place since November 2014 lends itself to range of interpretations that only those Job centre workers and managers with a strong cosmopolitan spirit or a marked critique of the workfare system may be able to resist.

The tougher rules for migrants willing to access benefits and the channelling of social entitlements should be read both in light of the wider anti-immigration climate and of the wider attack on welfare claimants under the spreading of the sanction regime. The notion of deservingness underpinning the functioning of the UK workfare regime cuts across the differentiation of citizenship, hitting both the migrant and non-migrant working poor. Indeed the notion of a genuine job seeker is part and parcel of that condition of ‘employability’ used more broadly as way to coerce people to precarious work, being it the case of the citizen or non-citizen ‘scrounger’. Yet, it is exactly out of this increasing intertwine of migration and welfare strategies of control that new opportunities for unity and cooperation have emerged across different parts of the migrant rights and unemployed groups.

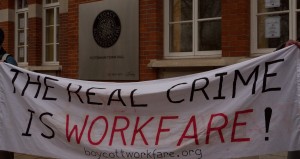

The ‘boycott workfare’ movement in the UK is growing in strength developing a variety of direct actions, campaigning, training and solidarity initiatives to oppose a system that attacks those who are already in a highly vulnerable position. It is also building an alternative narrative to replace the notion that those who are unable to work are ‘worthless’ and do not deserve access to welfare, rather highlighting how people on benefits are often those who carry out the important unpaid work of caring, parenting and keeping up their households and communities. Many pro-welfare groups across the country are showing how it is possible to build solidarity through support networks on the ground while denouncing the devastating effects that the punitive and oppressive measures of the workfare regime has on already isolated people, further constraining them to poverty, destitution and at times even death.

In Leeds, North West of England, a campaign group called Hands Off Our Homes originally set up to oppose the cuts and the punitive ‘bedroom tax’ for claimants of housing benefits, has started a campaign against welfare sanctions that also aims at involving pro-migrant rights groups worried about the growing climate of racism fuelling discrimination against migrant claimants. Under the slogan ‘Welfare for all’ activists from the newly formed Leeds Solidarity Network, an alliance of different groups working across welfare and migrant rights, are also challenging the scapegoating of migrants among working people and claimants themselves, in a context where the media and electoral speeches trigger social tensions. Their effort is to rather highlight the commonalities among migrant and non-migrant working poor showing how resisting the current attacks on welfare and strengthening worker and social rights for all, rather than opposing migration, is the way forward to fight precarity and the present regime of welfare and migration controls, in the UK as well as in Europe.

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione

∫connessioniprecarie connettere gli ∫connessi, produrre comunicazione